The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali are one of contemporary yoga’s favourite sources of inspiration and guidance on how to live a balanced and ethical life both on and off the mat. While the complete Yoga Sutras (written sometime in the first four centuries CE) consists of 195 aphorisms that yoga scholar David Gordon White calls “a Theory of Everything,” most of modern yoga’s attention is focused on the 31 verses that describe the ‘eight limbs’ of yoga, which form a practical guide on the subject of how to attain liberation from suffering. A study of the history of the Yoga Sutras reveals that much of our understanding of this ancient work has been filtered through numerous commentaries on the original verses. Our version of the eight limbs acknowledges the context of their creation and then finds ways to apply them in contemporary life.

Barbara Stoler Miller’s Yoga: Discipline of Freedom: The Yoga Sutra Attributed to Patanjali is the translation and commentary upon which our interpretations are based.

What are the 8 Limbs of Yoga?

• Yama

• Niyama

• Asana

• Pranayama

• Pratyahara

• Dharana

• Dhyana

• Samadhi

1. Yama (Restraints)

The yamas are five ethical precepts that outline a code of conduct that should be observed when interacting with the world around us. They offer guidance on how to act toward others. They are:

Ahimsa (Non-Violence)

Ahimsa probably had a very straightforward meaning to the original audience of the Yoga Sutras and its interdiction against violence is one that is, unfortunately, still very relevant today. In addition, some contemporary yogis interpret ahimsa as a directive toward a vegan diet on the basis that ‘all living beings’ are entitled to be treated with kindness and non-violence.

Satya (Truthfulness)

Telling the truth is a moral baseline we can probably all get behind and it’s certainly one that’s not outdated. In fact, in the age of institutionalized lying when ‘alternative facts’ (aka lies) are condoned in the most public sectors of society, it is more important than ever to speak the truth and support others who do so.

Asteya (Non-Stealing)

In Patanjali’s day, this was undoubtedly primarily an injunction against taking someone else’s property. While that continues to be good advice (not to mention the law), there are now so many more ways to steal, some of which may not be as obvious. Intellectual property, logos, pictures from the internet: whatever it is that doesn’t belong to you, leave it be. Originality is certainly a good choice for the modern yogi wishing to practice asteya.

Brahmacharya (Celibacy)

Brahmacharya is probably the yama that requires the most massaging to fit into a contemporary yogi’s lifestyle. Yes, it’s highly likely that the original intent was a total prohibition on sexual activity. Yoga certainly wouldn’t be the first school of thought to promote celibacy for its practitioners. Does that mean that’s how we have to practice it today? Fidelity, constancy, and having honest open relationships with our partners work as alternatives for today’s yogi householders.

Aparigraha (Non-Coveting)

Now, here’s one that (unfortunately) really stands the test of time, no modern filter necessary. Coveting what other people have, jealousy, envy, and greed are all words for the green-eyed monster that has apparently been with us since the beginning. It’s a tough one to get past. One thing that can help is to name the sensation when it arises so that we’re aware that it’s happening and are then able to realize that we don’t have to become attached to it.

2. Niyama (Observances)

If the yamas are outward looking toward society, then the niyamas are inward practices to improve the self. They are:

Saucha (Purification)

Purification of the body and mind are specified in the Yoga Sutras as a necessary step in detaching from the physical world in preparation for meditation. For us, this might mean identifying and releasing thought patterns that have the ability to distract us from our purposes. If we can clear away thoughts that dwell on negativity or meanness toward ourselves or others then there’s less clutter up there when it comes time for inner focus.

Santosa (Contentment)

Contentment is a real challenge for many people so it’s well worth examining why it’s so damn hard to feel happy with ourselves. The culture of always wanting more, of status, of constant striving to out-do is so pervasive that it actually takes a bit of effort to realise that it’s not compulsory. Existing in a state of constant dissatisfaction and comparison isn’t the only way. A practice of expressing gratitude can help us feel better about the good things we do (already) have in our lives.

Tapas (Asceticism)

One of the translations of tapas is heat, so it is often interpreted as encouraging practices that stoke our inner fire. Miller explains that asceticism was though to produce the heat of tapas. Purification through self-discipline is described in Patanjali’s work. In contemporary yoga, tapas might be observed through the daily practice of postures or meditation which require self-control to maintain.

Svadhyaya (Study)

Svadhyaya is sometimes translated as self-study, which implies that it means introspection, however, that doesn’t seem to be the original intent. Rather, it meant the study, memorization, and repetition of sacred prayers and mantras, which was and continues to be a common practice in Hinduism. In modern times, we may choose to interpret this as an exhortation to be diligent students of the world, whether through formal or personal education.

Ishvara Pranidhana (Dedication to God/Master)

This can be a tricky one since many modern practitioners bridle at the suggestion that God is a prescribed part of our practice. It’s interesting to note that the meaning of Ishvara in the original text is also open to interpretation. It could have meant a master, a teacher, or an unspecified god. Submission to a teacher is in line with the guru-student relationship that was an established tradition within yoga in India. However, surrender to a guru doesn’t sit that well with many Western students. For our purposes, we can perhaps think of it as a necessity to acknowledge that yoga is a spiritual practice. It affects the whole person, whose constituent parts are mind, body, and spirit.

3. Asana (Posture)

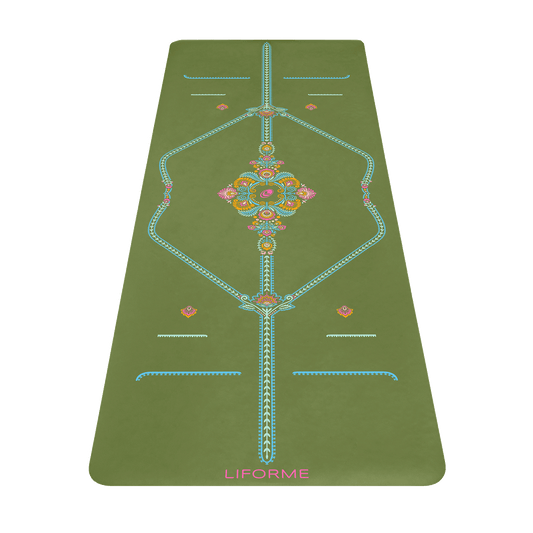

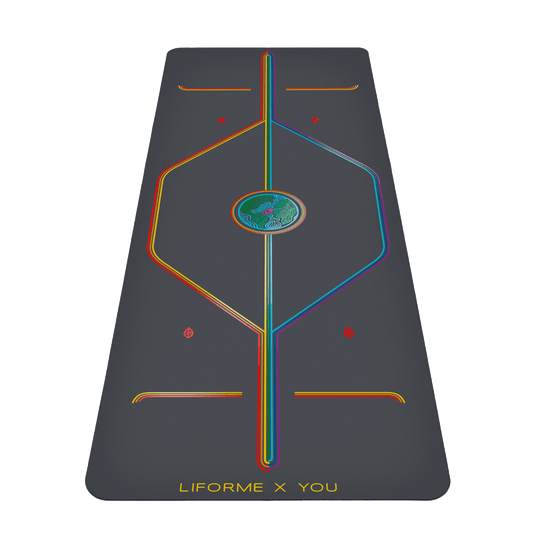

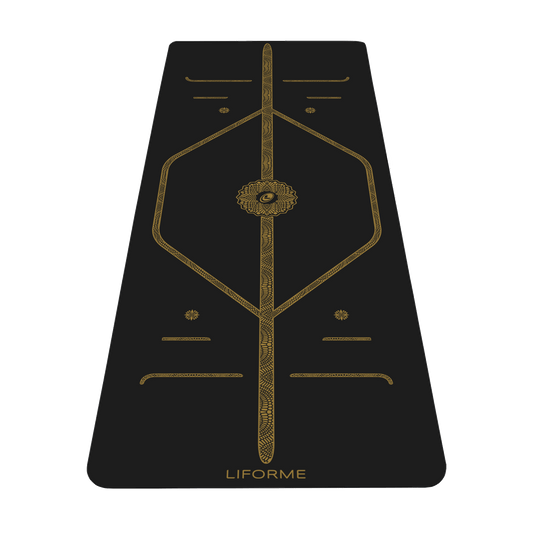

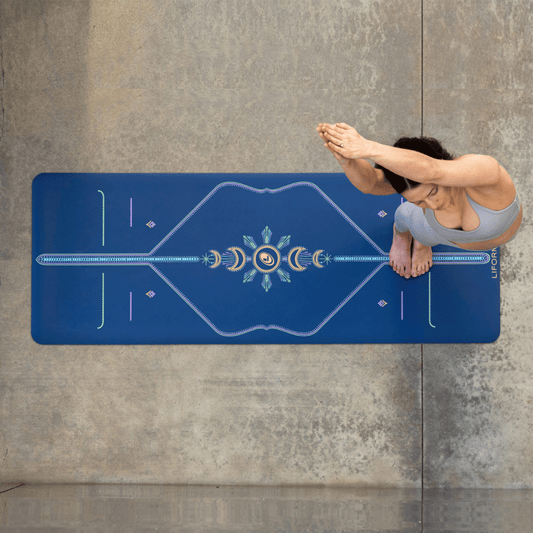

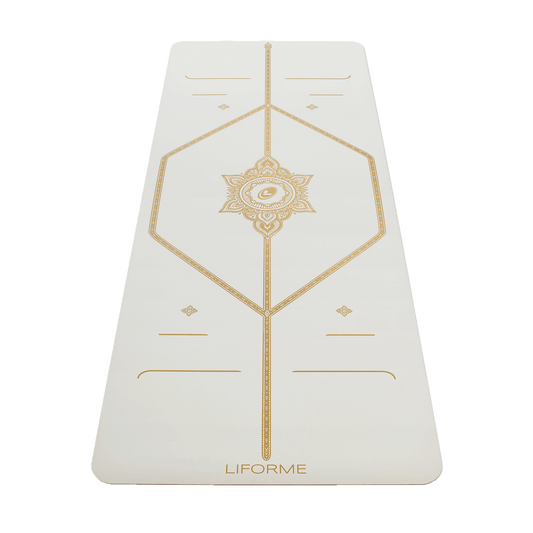

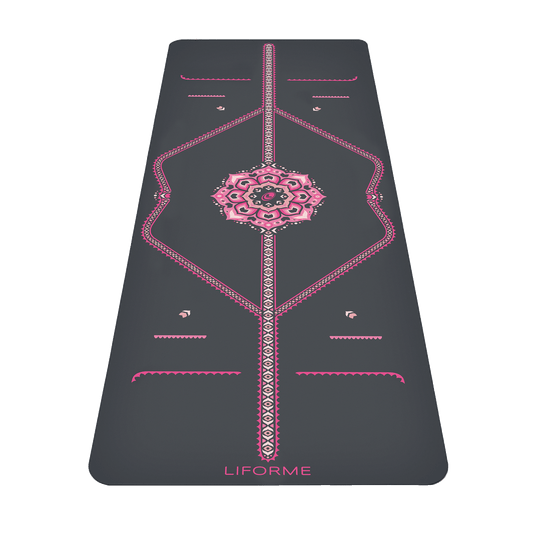

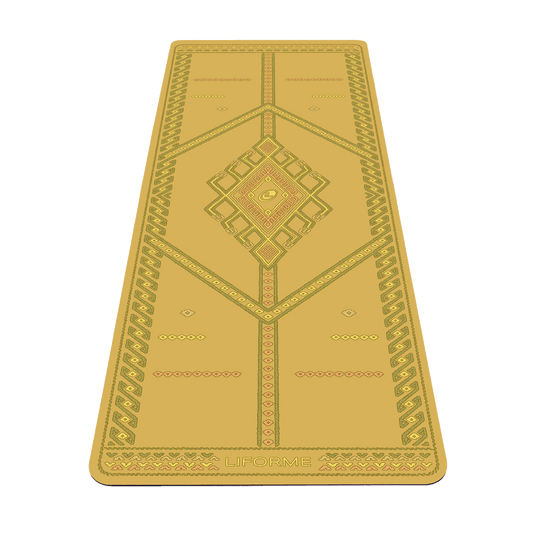

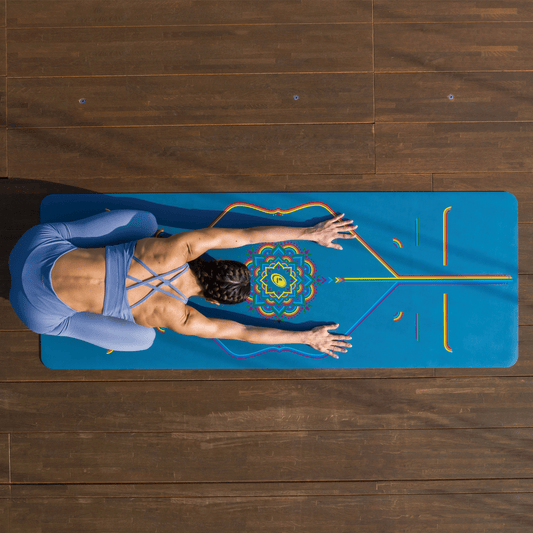

While it might seem like we’re getting onto more familiar ground here, asana also had a very different meaning in its original context. While we now use this term to refer to any part of a postural practice (all yoga poses), it’s original meaning was simply a comfortable seat. Patanjali’s work has no other asana instruction other than the necessity of finding a posture in which to engage in the practices of pranayama and meditation (see below). In terms of the eight-limbed path, it seems that once we have established that we are right with the world and with ourselves, we can turn our attention to the business of calming and focusing the mind. Of course, asana is now quite often the point of entry for people into yoga. Liforme yoga mats support the pursuit of asana by incorporating useful alignment lines.

4. Pranayama (Breath Control)

On the subject of breath control, Patanjali instructs that the practitioner should regulate the inhalations, exhalations, and retentions of the breath in a cyclical manner. All other breathing exercises we now practice came from sources outside of the Yoga Sutras. Since the eight limbs are concerned with preparing for meditation, any breath that is centering and brings us in contact with the present moment helps ready the body and mind to turn the focus inward.

5. Pratyahara (Withdrawal of the Senses)

Isolating consciousness from the distractions offered by engagement with the senses is the final physical preparation for the meditation practices outlined in the final three limbs. This can be in itself a form of what we would call mindfulness in which sensory input such as sounds, sights, or smells are noticed as external and then allowed to pass without capturing our attention.

6. Dharana (Concentration)

Dharana is the first stage in the inner journey toward freedom from suffering. During this type of meditation, practitioners concentrate all of their attention on a single point of focus such as the navel or on an image in their mind.

7. Dhyana (Meditation)

In this stage, the practitioner meditates on a single object of their attention to the exclusion of all others. While we are accustomed to a type of meditation that attempts to clear the mind of all thoughts and images, this doesn’t seem to have been a requisite part of the method described by Patanjali. As long as the attention is focused, the object is not specified.

8. Samadhi (Pure Contemplation)

When dhyana is achieved, the practitioner enters a state of samadhi in which they merge with the object of their meditation. Although this has been interpreted to mean union with the divine or with the entire universe, Patanjali’s explanation does not go this far.

Beyond the 8 Limbs

There is actually a further step in attaining liberation from suffering in Patanjali that doesn’t make it into most contemporary teaching. This state is called nirbija-samadhi, which Miller translates as seedless contemplation, in which the seeds are thoughts that beget other thoughts. While we might logically conclude that this is the cosmic union we associate with the culmination of the eight limbs, David Gordon White explains that the goal of the Yoga of Patanjali is actually the absolute separation of the human spirit from the matter of the world. When this happens, the spirit has the ability to expand infinitely and is capable of what we would call supernatural acts.

The application of the eight limbs has transformed tremendously from the time of their recording by Patanjali to our present moment. When these contexts are so radically different, it wouldn’t make sense to expect the limbs to fit seamlessly into contemporary yoga. However, this doesn’t mean that they have no place at all in our canon. There are many lessons about how to treat others and ourselves, as well as the value of deep contemplation that are still relevant and are a profound complement to today’s physical practices, even a millennium and a half after their recording.

Love,

Liv x

Sources:

Miller, Barbara Stoler. Yoga: Discipline of Freedom: The Yoga Sutra Attributed to Patanjali. University of California Press, 1996.

White, David Gordon. The Yoga Sutra of Patanjali: A Biography. Princeton University Press, 2014.